The first catastrophe of my life forged me in ways that are still surprising, in ways that are not readily apparent until I think: Oh, yes, it’s connected to that day in March. That’s what calamity does: it stops life from staying the same, it takes you, as the human you are, and teaches you that expectations are illusions, that to survive, you must adapt, sometimes, to the unthinkable. It is an essential pattern, similar to the rise and fall of tides, to the rhythms of inhaling and exhaling. Disaster removes, at least temporarily, the idea that we have control. What it leaves behind is the realization that time is a continuum: the event exists in your memory while staying with you in the present.

So back to that day in March: I was twelve and as the school bus slowed, I saw my favorite aunt waiting at my stop. It was Friday, gray and overcast and I knew she

sometimes took me for pizza or to the mall on dreary days so I was glad to see her. Only as I drew near her, she looked small and slightly frozen standing there. Had she

shrunk?

“I have something to tell you,” she said in a strained voice. I shifted my books to my other hip while my friends called goodbye and ran toward their houses.

I waited. Soft rain began.

“Your father is dead.”

And there it was. Those simple four words would forever delineate my existence: there was the stable, happy time when he was alive and now the surface beneath my feet had turned to water. I did not know that I could trust the pavement to hold me any longer. Nothing seemed real. I walked through the next days of his funeral and burial in an underwater dream. I don’t remember sleeping or eating or anything I said or that was said to me. Words and prayers bounced past me, colorful and rubbery in the way of a psychedelic dream.

When I returned to school, I no longer heard my middle school teachers. I had entered a strange realm where I had let go of assumptions. My entire world had slid out from my feet at that bus stop and I no longer knew what waited around the corner. I woke up at night and stood in the yard, looking into the sky. I couldn’t keep track of anything, not conversation or time or my lessons.

My teachers left me alone. My friends kept a friendly, sympathetic distance. My mother was working more hours after he died, and in her absence, alone in the

house, I had begun to see my father’s ghost walking past me. He said nothing, and he did not look at me: he simply walked past slowly and silently in the way you would

expect the dead to stroll.

I told my mother I had gone crazy.

“You can’t see a psychiatrist,” she warned me. “When you go for a job, they look it up and you’ll never get hired once they see you went in to that kind of doctor.”

I was in honors classes and our teachers already reminded us regularly that college was our future. I had not really thought about employment.

“Do you think they will look at my seventh grade record?”

“They look at everything.” She said this in the unconditional, absolute way that my teachers did when giving the correct answer. There was no room for questions.

I sat at the table after my mother got up and went to bed. I watched her cigarette burn in the ashtray. She no longer told me to go to bed at a certain time or asked me

about school. In a way, she was not present in her life any more than I was, but at twelve, thinking about someone else’s pain is momentary as weather.

I only knew one fact: Everything had changed. I remember thinking that no one, not my father or doctors or the teachers at my school could really protect me against a

tide that wanted to rise and engulf me.

—

My father had been methodical and strong, a person who organized nuts and bolts and screws into labeled coffee cans, who built shelves to hold brushes and paints in

the order they should be used. We lived near a beach so he stored boxes of canned food, candles and hurricane lamps in the event of flooding or power outages. He was a firefighter as a career, a person trained to douse fear and flames, to calm the public and give talks about safety.

When he went into the hospital, I only went to see him once and I was shocked. He was there for something rudimentary, a short stay, but when I saw him, he looked

thin and strange to me, as if the robust man I knew had been replaced by a hologram. I said I didn’t feel well, and went to the elevator to wait for my mother down in the lobby. An intern got in with me; I looked at him and began to cry.

“You know,” he said softly, “your dad is going to be fine.”

“No,” I said between quiet sobs, “he’s not. It doesn’t even look like him.”

“Maybe you’re just not used to seeing him when he’s not feeling well.”

“No. It’s not going to be all right.”

The intern leaned over and patted my shoulder. I pulled away from him. I may not have had the language for it then, but I do now: I felt the comforting words and the shoulder patting were condescending. How would anyone know what is going to happen? It may not be likely that a man in his forties would pass away, but nothing was guaranteed. And I had seen something in my father’s eyes that had terrified me: it was as if he was no longer there. Could doctors tell when people were leaving? Or could they only tell by certain measurable biological signs?

My father died three days after returning from that hospital stay. His doctor called to say how sorry he was and how terribly unexpected it was. He spoke briefly to my

mother and she got up and went into the other room and shut the door. I could hear her crying.

I began to get better. When my father’s ghost walked past, I didn’t look up. I sat at the table conjugating my Spanish verbs and answering history questions until my

mother came home from work. I began focusing enough in school to appease my friends and go back to answering correctly in class.

But I had changed. I no longer viewed my teachers as wizards or the police, or hospitals as spheres I could trust. They were places that wanted to make us believe we could have safety or knowledge or be healed, but they were more theater than reality. Most of what I knew, I had learned from my own reading, and all the key concepts school insisted on – like Manifest Destiny or how to determine a

hypotenuse – I saw as useless artifice to keep us busy for six hours. Crime rose as the police budget increased. Hospitals were places where people could measure

things, but they lacked the perception to understand how the human spirit determined so much of our biology.

And I had sharpened. This new acuity gave voice to a narrative presence that I relied on more than anything that authority instructed. I would go on to navigate the

world from that perspective, using my inner voice and intuition as a guide. While my school peers fretted over dates and driving permits, I drifted above those concerns

because I knew nothing really lasts and everything is impermanent. That belief allowed me to take risks that I do not believe I would have taken had I not been forced to be more independent and more resilient after my childhood world shattered.

And perhaps that is the subtle gift of catastrophe: it compels us to leave our residence of comfort and step into a place that is unfamiliar. We learn to rely on ourselves – on our insights – and to take the pain we carry to understand the world and the people around us with greater responsiveness and empathy.

Author Bio

Anne Spollen is widely published in the fiction and non-fiction realms and has authored two novels, both published by Flux. Twice-nominated for Pushcarts, she has just completed a middle grade novel. Currently, she is working on a book that traces a family member’s journey with addiction and how his available community, legal and medical resources unwittingly enabled his addiction. She lives in New York City, but spends a lot of time at the Jersey shore.

Tags

#resilience #spirit #healing

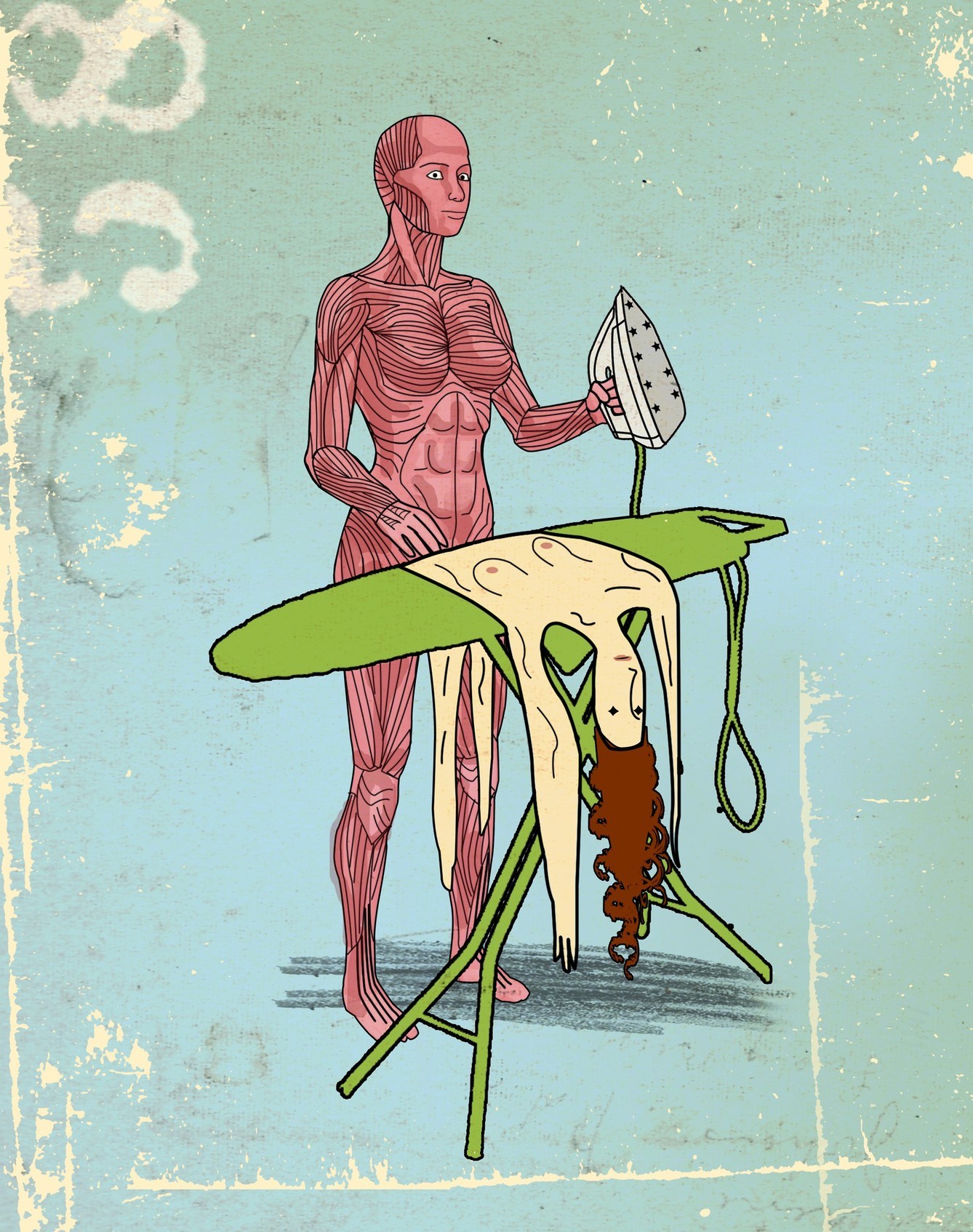

Image Credits

McConkey, Bill. “Skin.” Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/c45cxpaq.