I wake up and stretch in the dark on a rainy Monday morning in April in my childhood bedroom. As I walk down the creaky wooden steps to make myself oatmeal and coffee before logging on to my first Zoom class of the day, my eyes fall on the golden picture frame hanging next to the front door. Inside, velvety green cards with cursive engravings display my family member’s names with a description of their Old German meanings. Although my name has been legally changed, the card with my birth name still lurks behind the glass. A card with my new legal name, Aaron, was purchased but never added. It looms precariously on top of the frame, placed there with the intention of swapping it out for my old name. It never made it into the picture.

As I head into the kitchen for my oatmeal, I look up at an old photograph of myself. The young girl trapped in the picture is a stranger to the person standing before her now. As far as one can tell from inspecting the walls of my family’s home, a man named Aaron does not exist.

I carry my oatmeal and coffee back upstairs and situate myself at my desk, which is still crammed with papers from high school, a pile gradually building up to its inevitable tipping point. As hazy thoughts of semester work and the pandemic swirl around in my head, not yet freed from my brain by the caffeine, I glance up at the two bookshelves spanning my blue bedroom walls, scanning the spines of the books I devoured as a child.

Lately, my eyes are often drawn to my collection of worn-out Harry Potter books, their childhood magic as worn as their covers, the stories tainted by their author’s politics. Pushing away disappointment, my eyes fall to the red sharps disposal container sitting on the shelf below the Harry Potter books. A DANGER BIOHAZARD warning is printed in large font across the front, the used needle tips inside clack together as I push the container aside. Behind it sits a pickle jar filled with old 1 mL syringes. Mondays are my shot days. For the past year, I have been filling the red sharps container with used needles, the hormone injections slowly warding off disaster. I pull a fresh syringe out from its plastic wrapping.

—

On a warm summer afternoon one year ago, I sat in the confines of my small college dorm room in Baltimore, holding a 25 Gauge syringe in my shaking hands. I watched as small bubbles trickled in along with a steady stream of oily liquid. The testosterone solution is thick, hard to pull through the narrow needle tip. I hold the syringe upright, flicking it to coax the air bubbles to the surface and squeezing them out like the nurse taught me to do the week prior. I tuck my t-shirt under my binder to expose my stomach, prepping the skin with an alcohol swab. Then I jam the needle through my skin as quickly as possible. The sharp metal glides through the subcutaneous layer of fat and testosterone spreads through the adipose tissue. I do this weekly, with periodic blood tests measuring my hormone levels and confirming that my testosterone levels have increased thirty-fold. Gradually, my vocal cords thicken, lowering their vibrational frequency and giving me a deep voice. The testosterone activates the growth of facial hair and I begin to be perceived as male, undoing years of unwanted development and replacing it with a persistent sense of calm and comfort.

—

Now, I repeat the same ritual I have performed every Monday for the past year. The needle is my sculpting tool, allowing me to mold my biology and alter my secondary sex characteristics. Watching muscles fill in and my face change shape, I am struck by the magic of being trans. This magic can be read onto the Harry Potter texts, ascribing a certain queerness to the art of shapeshifting and time travel that expands the text beyond its original intent. In the same way that the meaning of text can be ever changing, so, too, can the body. Engaging in a visual epistemology, we read meaning from flesh. Just as with text, however, the true meaning often can only be found by reading between the lines, or, in the case of bodies, by looking within.

Returning the pickle jar of old syringes to my shelf, I think about how being trans has made me accustomed to living in a perpetual state of disaster preparedness. First as a woman and now as a trans man, I have learned to carry myself with a keen awareness of my positionality. Narrowed eyes and suspicious looks used to follow me into public bathrooms. I am hyper-aware of the way I walk and sit and dress and speak in public. Just as masks and gloves protect from the present virus, so my clothing and practiced movements offer me the protection of passing as a cisgender man in a world where to be otherwise is dangerous. Navigating public spaces in the current moment of social distancing and heightened caution requires a hyper-awareness of one’s surroundings. Armed with hand-sanitizer and surgical masks, we shield ourselves from pathogens, careful to go out of our way to avoid people. Public spaces have turned into a minefield of contagion and disease for the general public; for trans people, these spaces have always been a minefield.

As we collectively learn new ways of navigating a dangerous world that requires a heightened sense of bodily awareness, I am reminded of another lesson that many trans people learn at a young age: disaster can be a gradual process. Puberty unfolded in front of my eyes like a slow-motion car crash that I was powerless to stop, estrogen wresting my body away from me. When disaster is inevitable, it is easy to succumb to it.

Sitting at home, waiting for it to be safe to go outside again, I am used to feeling caged. For years, I lived under the weight of a society that placed me into the box of femaleness and womanhood against my will. Being quarantined — being closeted — is lonely and isolating. It is a mechanism of protection and self-preservation in response to danger. It takes a mental and physical toll. Disaster becomes embodied when we take on its weight in our temples, in our backs and aching joints, and in our guts. I can feel the tension stored in my body. Just as disaster creates trauma that can leave physical traces in the body, so transitioning has left its marks on me. From the tiny dots of scar tissue that line my stomach from weekly injections of testosterone, to the red scars that cross my chest from reconstructive surgery, my body carries the physical evidence of the battle for survival.

Trans people have been pathologized, medicalized, marginalized, and stigmatized, so it is only to be expected that the narrative forced upon us is one of suffering, of dysphoria, of feeling trapped. For me, writing from the current moment of disaster does not only mean writing from a world of coronavirus, it also means writing from a world where in the last months, several trans people were murdered and the president announced the erasure of civil rights protections for transgender people in healthcare. It means writing on a desk stacked with legal and medical paperwork collected from months of petitioning the court and government agencies to change my name and gender in their records, remnants of an ongoing struggle for legal recognition. It means writing after my essential, but apparently-not-essential-enough gender confirmation surgery was put on halt for months.

In the face of these disasters, the work of survival is a daily task. To imagine a viable future for myself as a trans person amidst the chaos, I find it essential to ground myself in the details of my daily, embodied reality. For years, I chose to ignore the physical reality of my body. Now, as I write from the current moment, I choose to lean into every detail.

—

Months after that rainy Monday in April, I still find comfort in the daily habits of survival. A new semester has begun, and I again find myself descending the stairs to prepare my warm morning oatmeal and coffee. The card with my birth name written on it still hangs on the wall, and I catch myself throwing a cursory glance at it, wondering whether it will ever be replaced. Then, I continue past the frame and down the stairs. Whether or not the name card will ever be removed, the writing on the wall is beginning to feel irrelevant. My current physical reality is already written all over my body, inscribed by testosterone and time, and the language of my body is all that I need.

Author Bio

Aaron Wiegand is an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins majoring in Biomedical Engineering and minoring in the Study of Women, Gender and Sexuality. His interest in the intersection of medicine and the humanities motivates his research in diagnostic disparities and his work both as a patient advocate and as a volunteer for the Baltimore Transgender Alliance. Aaron currently resides in New Jersey and is planning to attend medical school after graduating, where he hopes to continue using writing as a form of advocacy and consciousness-raising.

Tags

#embodiment #gender #transition

Image Credits

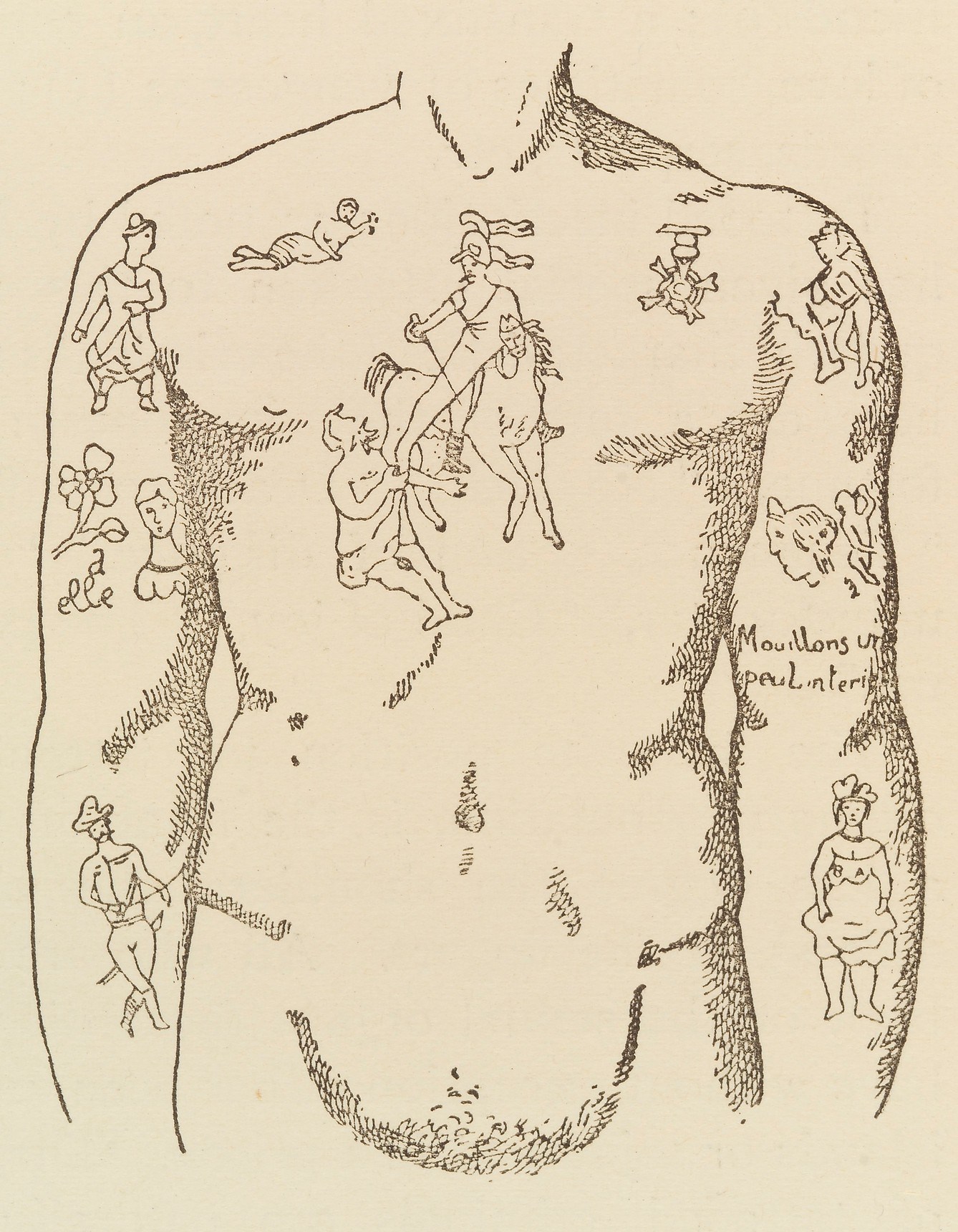

“Tattoos on the body.” Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/e45y3v4d.